HOSTED

Artists of the Kabri Cooperative Gallery

hosted at Alfred Gallery

Ashraf Fawakhry, Gabriella Willenz, Josyane Vanounou, Dubi Harel, Drora Dekel, Ziv Sher,

Yael Cnaani, Linda Taha, Miki Zadik, Muran Daaka, Noam Ventura, Sahar Miari, Raghad Sawaed, Shlomi Haggai, Tamar Hurvitz Livne

Curators: Josyane Vanounou and Tamar Hurvitz Livne

9.1.2026-7.2.2026

The Kabri Gallery is a Jewish-Arab cooperative art gallery located in the Galilee. Although it was closed during the war due to its proximity to the northern border, its exhibitions were hosted at the Wilfrid Israel Museum at Kibbutz Hazorea and the Givat Haviva Gallery. In order to strengthen ties between the periphery and the center, Kabri Gallery hosted the Alfred Gallery in December 2025, and now the Alfred Gallery will be hosting fifteen artists from the north

The act of “hospitality” involves questions of ethics, philosophy, morality, and culture. Hospitality is an intercultural encounter, a meeting with the “other” that takes place on the threshold—at the door, at the border, at the point of transition. Yet beyond the encounter, it also involves uncertainty, danger, anxieties, and power relations. These issues are part of the gallery’s routine and the conversations among its Arab and Jewish artists. Who is hosting whom? What is this partnership? The complexity of the issue is also expressed in the fact that the name of the exhibit (“Hospitality”) contains within it the danger that “hostility” will develop; but there is also opportunity within it. As Jacques Derrida wrote: “An act of hospitality can only be poetic.”

The “Hosted” exhibition is an identity card for the Kabri Cooperative Gallery. It features video works, sculpture, photography, painting, and prints by fifteen artists who hold fast to the belief that divisions and disputes can be eliminated through the language of art. In addition to the artwork, the exhibition presents a new film featuring conversations among the artists on the subject of partnership. The exhibition is a collective made up of individuals—each artist presents a single work. Thus, a rich diversity of voices is created, one that is not necessarily harmonious—there are paradoxes within it—although it enables listening, freedom of renewal, and dialogue.

Kabri Gallery was the first gallery in the kibbutz movement. It was founded in 1977 by the sculptor Yehiel Shemi and other members of the kibbutz. Since 2012, the gallery has operated as a Jewish-Arab cooperative gallery—the only one of its kind in Israel and worldwide. The gallery serves as a home and a platform for artists from the Galilee and for works that promote shared living. Kabri is a kibbutz that is identified with the visual arts, in the spirit of the artists Uri Reisman z”l and Yehiel Shemi z”l who left their mark on the kibbutz.

Miki Zadik’s woodcut combines engraving with drawing on paper on both sides. Zadik engages with everything above and below the waterline. She seeks to find balance, through a quiet movement based on horizontality. Despite the lack of symmetry, a vertical equilibrium exists in the work. The eye delights in the apparent balances, while the threat rising from the depths unsettles it.

Ziv Sher presents a digitally manipulated photograph, entitled “#2,” from a series entitled “Cloudburst.” The series is composed of layers of images from the destruction in Gaza. The images underwent disassembly, melting, joining, and reconstruction, until a new space emerged from them—one that is abstract and formless—a space containing signs and remnants.

Gabriella Willenz presents a digital collage entitled “The Herzls.” It shows bearded men in layers, in the pose of Theodor Herzl gazing from the balcony in Basel (1897). The image that took root as a cultural icon of the Zionist vision remains seared in our consciousness, yet its utopian meanings are steadily eroding. The photograph contains portraits of thirty men—religious, secular, Arab, Jewish, hipsters, and others—laid one atop the other. Thoughts arise about recurring fashions and about similarity and differences among men that are located around the same imagined average.

The video entitled “Metamorphosis” by Dubi Harel is based on similarities in the visual structures of a bouquet of flowers, a leafy tree, a cloud of smoke, and an atomic mushroom cloud. The atomic mushroom cloud is an image that has often recurred in the artist’s work over the past decade. The transitions in the animation are built from dozens of engravings and drawings created by him, and they transform against the background of a peace protest song by Pete Seeger (in the form of a well-known Hebrew translation by Haim Hefer) entitled “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.” The contrast between the images and the song, which deals with the cycle of life and death, creates a new, contemporary meaning.

“Hut on the Kibbutz” is the title of the painting by Noam Ventura, which depicts one of the first homes built in Kabri in the 1950s. It one of the remaining Swedish prefabricated huts brought to the country at the beginning of the settlement period. The painting expresses the utopian simplicity of the kibbutz and reflections on the mobility of material. According to Ventura, “It is a historical view of what in my mind is an incontrovertible fact.”

The painting “Flame” by Shlomi Haggai belongs to the series entitled “Pastoral” whose images appear as though taken from the visual language of Italian Renaissance painting. The source of the image is a frame from an action film, but its translation into oil painting slows the moment of action and blunts the immediate drama. The flame fills almost the entire pictorial field, yet it is not rendered with realistic sharpness: its boundaries waver, the color breaks apart, and the image appears slightly pixelated—moving between clear recognition and abstraction. The fire does not erupt; it exists as a presence suspended in

time, as testimony to an event not fully depicted. Thus, a familiar and charged image is created, one that refuses to resolve into a clear narrative. A visual idyll and an image of danger coexist within the restrained language of painting, placing the very act of observation at the center.

A quiet, almost everyday act—that of a pair of hands sewing a line into paper—appears in the video by Muran Daaka. As one’s gaze lingers, something else begins to emerge: a subtle, almost invisible friction between a touch that heals and a touch that penetrates. The work invites the viewer to draw closer, yet at the same time unsettles him. The cyclical noise of the sewing machine, the attention to the texture of the paper, the hands that do not reveal a face—all of these create a troubling sense of intimacy: it seems as though the stitched line might at any moment jump out at the viewer. Is this an act of creation or of intrusion? Of tenderness or of control? Of repair or rather of exposure? In this space the material is vulnerable, the hands precise, and time repeats itself.

Linda Taha deals with the individual in his intimate surroundings, while aspiring to self-revelation. She is inspired by her biographical world and gazes directly at the image of the Arab woman. The painting, entitled “Self-Portrait”, is painted from within the courtyard of the Al-Jazzar Mosque in Acre. Linda’s head is covered with a scarf out of respect for the sanctity of the place. The recurring motif of olive leaves and branches appears in gold and serves as a barrier or a net between the artist and the viewer. For her, the olive leaves symbolize a connection to her roots and to the land. The color gold symbolizes sanctity and esteem.

Drora Dekel presents “The Cult of Life,” a painting created in the wake of another of her works that dealt with the cult of war. The work presents a secular ritualism, a desire for life and freedom bound up with dread and turmoil. The technique, combining collage and painting, adds to the sense of restlessness. The heroines of the painting are women, some of whom are based on the ritual of harvesting the Omer in the fields of Ein Harod in the 1920s. A wild bush at the center extends beyond the bounds of creation. A bird of prey rests upon the bush as a reminder of danger. There is a particularly small and threatening silhouette in the form of a man which appears threatening—perhaps a running soldier. The pomegranates, like wine, enable the joy of living.

The artist Ashraf Fawakhry responds to the iconic painting by Uri Reisman, entitled “House on a Hill.” Fouakhri looks at Reisman’s work with great admiration and is influenced by his coloristic approach. He places a donkey—a symbol identified with his own work—on the roof of Reisman’s house. The donkey converses with the figure of the fiddler on the roof who appears in paintings by Marc Chagall. From its position, one can look out over the space between Acre and Rosh Hanikra—to the village of al-Bassa (Batzet), from which Fouakhri’s family was expelled in 1948, and to the village of Mazra’a, where Fouakhri was born. The village of al-Bassa also appears in the hologram image, which changes as the viewer moves, revealing the complex reality of life here in Israel.

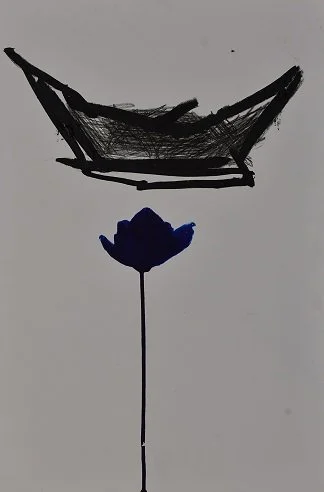

Yael Cnaani has in recent years worked with drawing on cardboard in ink, graphite, and printing ink. The gestures of drawing and movement stand at the center of her works. Cnaani perpetually draws lines between diverse spaces using a bare and modest language. In this untitled work, minimal touches of printing ink and graphite on cardboard create images of a flower and a boat.

The painting “Wing” by Josyane Vanounou is part of a project that began after October 7th. It is the wing of a crow—a wing as development, a sign of contraction. One wing, without a body, without movement—only memory—an isolated wing conversing with the classical wing of the Greek goddess of victory in the sculpture of Nike of Samothrace. In this sense, Vanounou’s wing embodies the tension between the movement of a free wing and a monument.

Saher Miari, an artist-builder and expert in construction and formwork, created the sculpture “Veins” on the well-known Alfred Gallery stage. Miari uses colorful industrial plastic pipes that burst from the wall and return to it. He seemingly exposes an inner view of the hidden plumbing within the walls of a home. Using the aesthetic language of construction that he has developed, he raises the issue of neglected public infrastructure in Arab villages and the figure of the Arab laborer who is building the country. Saher is capable of building a temporary home wherever he is located.

Tamar Hurvitz Livne explores the connection between sports and art in her work “Basket Home.” It was created while she was living at the Wingate Institute as an evacuee during the war. For her, sports is a utopian cultural space. A boundless desire to play sports is embodied in a spinning ball. The fabric is taken from the iconic “Kippi slippers,” produced at Kibbutz Dafna in the north and etched in our memory as an expression of warmth, home, Israeli identity, and simplicity. According to the artist, this is a memory of the house slippers she wore all day in her youth, in an attempt to hold on to and preserve an unattainable feeling of home that is absent and violated. The work expresses longing. Sport preserves values of hope. The fabric was donated by the Dafna factory.

Raghad Suwaed presents “The Generative Body.” This is a treated ready-made, a detail from a large presentation featuring eight lifebuoys and bells. The artist encountered a lifebuoy while wandering through an abandoned swimming pool. The buoy lay broken at the edge of the lifeguard station. For her, the buoy is a wreath of mourning. It carries the burdens of the period—despair and sadness without the hope of rescue. The buoy is a temporary place where one is permitted to exist, to breathe with its help, but not truly to live. The buoy does not save; it is a hollow, solitary object that postpones collapse so that one can continue to hang on and remain in the same marginal place.

Curators: Josyane Vanounou and Tamar Hurvitz Livne